Translation Request: Norwegian

Comments

-

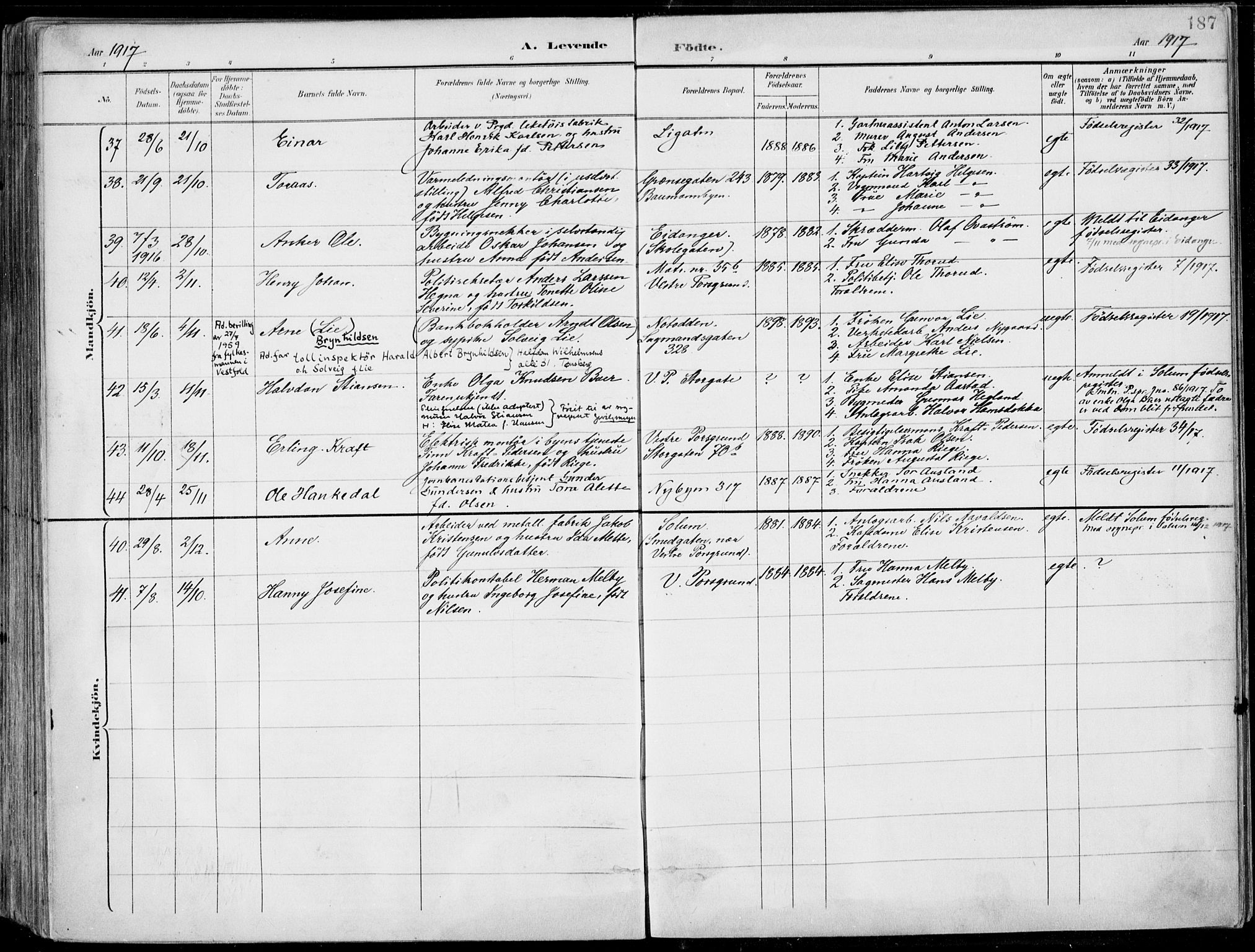

In the box for parents it says "Widow Olga Knudsen Baer, father unknown. Foster parents (not adopted) bricklayer Halvor Stiansen, wife Eline Matea born Hansen."

After the bracket it states the notation regarding the foster placement "Added by [probably some legal title and the person's last name."

The final column it says "Recorded in (more literally: notice place in) Solum birth register." Then some legal notice about Olga and the unnamed father.

0 -

Thank you @Gordon Collett. I also wanted to figure out that last sentence: To av enke Olga Buer utlagte? fadre is? ved dom blït? forfundet?.

Also, if he was just taken in by this couple as a foster child and not adopted, why was he given their surname? Was that common in foster situations? The man lived to age 70 and kept the surname.

0 -

Here's what google gemini made of my reading or misreading.

"To av enke Olga Buer utlagte fadre is ved dom blït forfundet." translates to

"Two fathers named by widow Olga Buer have, by judgment, been fined/found responsible."

The sentence delves into a legal matter. This sentence uses archaic legal terminology common in older Norwegian documents. The term "utlagte fadre" refers to men who have been formally named as the father of a child born out of wedlock by the mother. In this case, the widow Olga Buer named two men. The phrase "ved dom" indicates that a legal judgment was passed.The word "blït" is an older spelling of "blitt," meaning "have been." The most challenging word, "forfundet," is not in modern Norwegian usage. However, based on historical linguistic context and related words, it most likely means "found" in the sense of being "found responsible" or "fined." Therefore, the sentence indicates that a court ruled on the matter, and the two men named by Olga Buer were likely legally declared the fathers and probably ordered to pay child support.

Thoughts?0 -

The translation looks good and seeing the transcription makes it much easier to read the original except for two concerns. One trivial error in the transcription is the "er" which is the first word of the last line which got transcribed as "is." The other is that last word. Is it really "forfundet" or is it "frifundet" (found innocent) which would change to meaning dramatically. Seems a bit funny to have two men both found guilty.

Surnames in Norway were very flexible prior to the mid-1900s. I don't know your background so I'll give a brief summary.

Norwegians throughout history had four types of surnames that were used:

- Patronymics - based on father's first name, would change in each generation. E.G., the children of Johan Hansson would be Johansson or Johansdatter.

- Fixed patronymics - based on an ancestor's patronymic, would stay fixed from generation to generation. E.G. the children of Johan Hansen would be Hansen.

- Farm names - used by farm owners, would change each time someone moved from one farm to another. E.G., the children of Johan Høyland of Høyland farm would all be Høyland until the family moved to the Lunde farm then he would be Johan Lunde and all the children become Lunde. If a child moved away from the farm to become a tradesman would often keep the farm name.

- Family names - last names such as Hagerup or Rustung that the family used for generations and would never change. Some of these had legal restrictions on who could use them.

In the early 1900s some laws were passed to require families to adopt a fixed, unchanging surname. The initial laws were pretty much ignored. In 1923 a major naming law was passed that required families to decide what their last name was going to be, how it would be spelled, and to quit changing things. The chosen last name could be a fixed patronymic, a farm name, or a family name they either had the legal right to or one they wanted that had no legal restrictions.

Since Halvdan was born at the time of these changing customs with last names, whoever was in charge of such probably just declared what his surname would be. What's kind of peculiar is that Halvdan's christening record includes that last name so it must have been decided for him very early what his last name would be. Since his father was not known, he could not have a patronymic or fixed patronymic, he wasn't living on a farm, and maybe the authorities didn't think much of his mother and didn't want him saddled with the last name of Baer so maybe all the traditional ways of getting a last name were ruled out and Stiansen was handy. I suspect this will be a mystery you will just have to live with.

0 -

@Gordon Collett, thanks again. I agree, the word was frifundet. For grins, I tried uploading a screenshot of the text to Google Gemini and it was able to interpret the image and provided a complete text and translation which verified it. The 2 men named by Olga were acquitted. The ability of the AI to interpret the handwriting was impressive.

Also, thanks for the information on naming in Norway. Until recently, most of the research I've been doing has been when patronymics were in use, so this is helpful. Olga's parents and siblings seem to be living during the transition period in this particular area. The family used fixed patronymics for a while with the surname "Hansen", then they later started using the family name "Eriksen". I've found records of the same individuals using the different names. In FamilySearch, I've been using the fixed patronymic as the birth name and the family name as an alternate name. Is there a convention I should be using for this situation when I record the information? Also, one of the sons appears to have kept the fixed patronymic "Hansen" as his surname and never used "Eriksen".

0 -

The surname situation can get really confusing. And these four types of surnames were used as least as far back in the 1700s. You can find plenty of fixed patronymics in the 1815 census for Bergen. So it takes some care even then to not get confused between actual patronymics and fixed patronymics.

The only convention I support is to be consistent and add as much information as possible. I like to use the Norwegian -son for true patronymics (you see -sen in the parish registers because the priests were either Danish or Danish educated but that is not what the local people actually said) and the Danish -sen for fixed patronymics since due to the Danish government and clerical influence nearly all fixed patronymics use the Danish spelling.

My wife is from western Norway which is very rural and so almost everybody had a farm name. So I tend to do the following:

A. In Vitals:

- In the first name field - first name and patronymic if used (You generally did not use a patronymic if you had a fixed patronynic. If you had a farm name you generally always used a patronymic. If you had a family name whether you used a patronymic depended mainly on your social status. Just a merchant? Yes. Government official or ecclesiastical position or noble? Then no.).

- In the last name field - farm name or fixed patronymic or family name that was used by the family at the time of the child's birth. (This is what the Geni website recommends, by the way.)

Using the full name in Vitals is really helpful because otherwise you get pedigree charts full of multiple Ole Olssons and multiple Hans Hansson and it is really to tell at a glance who is who.

B. In Other Information - alternate names:

- In the first name field - first name.

- In the last name field - patronymic. (This is because most indexes drop the other surnames and only have the patronymic. I want to make sure the hint engine can do the best job possible.)

- In the first name field - first name and patronymic if used.

- In the last name field - another surname the person used.

- Keep repeating until all important names used are include.

With exceptions as seem reasonable. If a couple lived with one of their parents when first married, had one child, then moved to their own farm and had a bunch more children, I'll go ahead and use the name of the second farm for the child's farm name under vitals just so the listing of the family isn't too confusing.0 -

Just a warning: Sometimes you will run across people who claim that a farm name is not a name but rather only a residence. That is not true. Farm names are true surnames derived from the residence. That they changed when one moved did not make them less of a name. Having one was a mark of social standing because only farm owners and their families used them, not the poorer tenant farmers.

The Norwegian Archives website in an English article on beginning genealogy research it states the following:

Norwegian names today are composed of a first and last name, as in other western countries, but in the 19th century, a name acted as an important clue to someone’s place on the family tree. The typical 19th century Norwegian name would be composed of three parts: The given name, the patronymic and the farm name. Let’s take an example and break it down: Peder Johnsen Berg, a typical Norwegian farmer of the 1800s.

Given names were normally of Northern European origin, often adjusted to suit local dialects. Also, spelling was not standardized, meaning that Peter, Petter, Peder or Per may very well be the same person recorded by different clerks. The second name, the patronymic (Greek for “father’s name”), is what most people associate with Nordic names today. These are the names that end in “-sen” or “-son”, meaning “son of”, thereby communicating who your father was. Consequently, Peder Johnsen is the son of John. His sister will be called Johnsdatter (John’s daughter), and his son will be called Pedersen. Upon arrival in the States, this would commonly have been altered to Peterson. Two Petersons are therefore not necessarily related, they both just happened to have a father named Peter. People would also include a farm name. As with the patronymics, these were not names in the modern sense. They were more or less an address. If you moved, the name changed. If Peder moved from the Berg farm to the Vik farm, he would be known as Peder Johnsen Vik, or some variant spelling, from then on. Practically all farm names were derived from a defining geographical feature. The most widespread names in Norway even today are Berg (mountain or outcropping), Haug (hillock), Hagen (outfield) and Dal (valley). Compound names, like Øvreberg (Upper Berg) or Djupdal (Deep Valley), continue to be common.

An encyclopedia of Norwegian farm names, developed in the early 20th century, can be digitally accessed here: tinyurl.com/farm-names. By the early 1900s, the old naming system was fading away due to industrial development and urbanization. Its fate was sealed in 1925, when hereditary family names were made mandatory. To this day, most Norwegian last names are patronymics or farm names from that period. ( )

0 -

And thanks for the evaluation of Gemini. Rootstech had a lecture about various handwriting interpretation and translation programs. It was pretty impressive.

0